By Felina Silver (copyright 2026)

Introduction: Why Some Towns Become Cities—and Others Don’t

Pull Quote: Urban success is not guaranteed by growth alone—it depends on adaptability, planning, and resilience.

Suggested image: Historic map of U.S. urban growth or a 19th-century railroad expansion map.

Urbanization has shaped the economic and social landscape of the United States since the nineteenth century. During westward expansion, industrialization, and resource booms, thousands of towns appeared on the American map. Yet only a fraction evolved into stable, long-lasting cities. Many others stagnated, declined, or vanished entirely.

Understanding why some towns successfully made the leap to cityhood while others failed matters today more than ever. Contemporary challenges—deindustrialization, population loss, climate risk, and fiscal stress—mirror historical processes that shaped earlier urban outcomes. By examining past town-to-city transitions, we can better understand what makes urban places resilient or vulnerable.

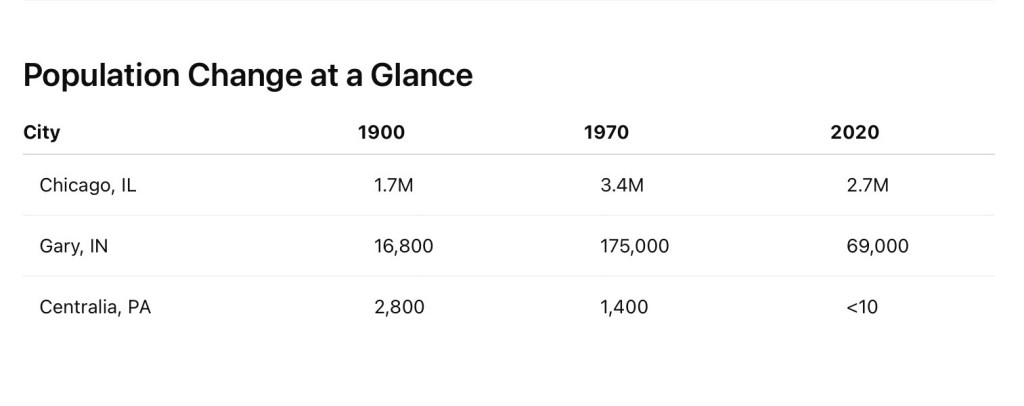

This article explores three contrasting U.S. cases: Chicago, Illinois, as a model of successful urban transition; Gary, Indiana, as an example of industrial rise and decline; and Centralia, Pennsylvania, as a town undone by environmental disaster. Together, they illustrate how economic diversity, infrastructure investment, governance, and adaptability determine long-term urban success.

What the Research Says About Urban Growth and Decline

Scholars of urban development consistently point to economic structure and infrastructure as key drivers of city growth. Early urban theory linked city formation to transportation networks, industrial clustering, and access to labor—factors that were especially powerful during the Industrial Revolution.

More recent research expands this perspective by examining long-term urban scaling and resilience. Studies show that cities with diversified economies are better equipped to withstand economic shocks, while cities dependent on a single industry face higher risks of collapse. Burghardt et al. (2024), for example, demonstrate that while urban infrastructure growth follows predictable long-term patterns, monocultural economies leave cities especially vulnerable to disruption.

Urban planning and governance also play critical roles. Landmark efforts like the 1909 Plan of Chicago illustrate how coordinated investments in transportation, public space, and infrastructure can support sustained growth. In contrast, cities that expanded rapidly without long-term planning often encountered overcrowding, environmental problems, and fiscal strain.

Research on urban decline further highlights the effects of deindustrialization, suburbanization, and disinvestment—particularly in twentieth-century Rust Belt cities. Environmental disasters represent an extreme but important category of failure, showing how external shocks can permanently undermine urban viability.

Taken together, the literature suggests that growth alone does not guarantee urban success. Adaptability, institutional capacity, and economic diversity are what ultimately sustain cities over time.

Method: Comparing Urban Trajectories

This article uses a comparative historical case study approach. The selected cases represent divergent outcomes in town-to-city transitions:

- Chicago, Illinois – a successful and resilient urban center

- Gary, Indiana – a city shaped and weakened by industrial dependence

- Centralia, Pennsylvania – a town effectively erased by environmental catastrophe

The analysis draws on U.S. Census data, historical planning documents, and academic research to trace long-term population and economic patterns.

Case Study 1: Chicago, Illinois — A Model of Urban Success

Pull Quote: Chicago turned disaster into opportunity by rebuilding with modern infrastructure and long-term vision.

Suggested image/map: Early 20th-century map of Chicago railroads and waterways; photo of post–Great Fire reconstruction.

Chicago’s rise from a small frontier settlement to a global city is one of the most striking urban success stories in U.S. history. Incorporated in 1837, the city benefited enormously from its strategic location linking the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River system.

Railroads, manufacturing, meatpacking, finance, and later services formed a diversified economic base that allowed Chicago to grow rapidly while remaining adaptable. Even catastrophe became an opportunity: after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the city rebuilt with modern infrastructure and new building technologies.

Long-term planning further reinforced Chicago’s trajectory. The 1909 Plan of Chicago promoted coordinated transportation systems, expansive public spaces, and civic design—laying institutional foundations for sustained growth. By the early twentieth century, Chicago had become one of the largest and most economically resilient cities in the nation.

Case Study 2: Gary, Indiana — The Limits of Industrial Monoculture

Pull Quote: A city built around one industry can rise quickly—and fall just as fast.

Suggested image/map: Historical photograph of Gary steel mills; population change graph over time.

Founded in 1906 by U.S. Steel, Gary was designed as a company town centered almost entirely on steel production. For decades, this strategy appeared successful. By the mid-twentieth century, steel mills employed tens of thousands of workers, and the city’s population soared.

But Gary’s dependence on a single industry proved to be its greatest weakness. Beginning in the 1960s, automation, global competition, and declining demand led to massive job losses. Population decline soon followed, straining municipal finances and accelerating infrastructure decay.

Racialized migration patterns and suburbanization further deepened disinvestment. Without economic diversification or adaptive planning, Gary struggled to reinvent itself. Today, it stands as a powerful example of how industrial monoculture can undermine long-term urban sustainability.

Case Study 3: Centralia, Pennsylvania — When Environmental Disaster Ends a Town

Pull Quote: Some towns don’t decline—they become uninhabitable.

Suggested image/map: Map of Centralia mine fire area; photo of abandoned streets or smoke vents.

Centralia represents an extreme form of urban failure. Founded as a coal mining town, its fate changed dramatically in 1962 when an underground mine fire ignited beneath the community.

Despite numerous attempts to extinguish the fire, toxic gases and ground instability made the town increasingly unsafe. Government buyouts and relocation programs followed, and residents gradually left. By the early twenty-first century, Centralia had effectively ceased to function as a town, with fewer than a dozen residents remaining.

Centralia’s story underscores a critical lesson: some urban failures are driven not by economics or governance alone, but by environmental shocks that permanently compromise habitability.

What These Cities Teach Us

Comparing these three cases reveals clear patterns:

- Economic diversity matters. Chicago’s varied economy allowed it to adapt; Gary’s dependence on steel left it exposed.

- Infrastructure and planning matter. Long-term investment and coordinated governance supported Chicago’s resilience.

- Environmental risk matters. Centralia shows how unchecked environmental hazards can erase a community entirely.

Urban success, in other words, depends not just on growth, but on adaptability and institutional capacity.

Conclusion: Lessons for Today’s Cities

Pull Quote: Cities that endure are those that plan for change before change is forced upon them.

Suggested image: Contemporary skyline juxtaposed with abandoned industrial site.

The American experience shows that the transition from town to city is never guaranteed. Cities that endure are those that plan for the long term, diversify their economies, and manage environmental risks proactively.

For contemporary policymakers and planners, these historical lessons are highly relevant. In an era of climate change, economic restructuring, and demographic shifts, urban resilience depends on learning from both success stories like Chicago and cautionary tales like Gary and Centralia.

Population Change at a Glance

References

Burghardt, K., Uhl, J. H., Lerman, K., & Leyk, S. (2024). Universal patterns in the long-term growth of urban infrastructure in U.S. cities from 1900 to 2015. arXiv.

DeKok, D. (2000). Unseen Danger: A Tragedy of People, Government, and the Centralia Mine Fire. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Smith, C. (2009). The Plan of Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

U.S. Census Bureau. (1900–2020). Decennial Census of Population.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Gary, Indiana.

Leave a comment